Abu Anis only realised something unusual was happening when he heard the sound of explosions coming from the old city on the western bank of the Tigris as it runs through Mosul.

Abu Anis only realised something unusual was happening when he heard the sound of explosions coming from the old city on the western bank of the Tigris as it runs through Mosul.

By Jim Muir

BBC News

"I phoned some friends over there, and they said armed groups had taken over, some of them foreign, some Iraqis," the computer technician said. "The gunmen told them, 'We've come to get rid of the Iraqi army, and to help you.'"

The following day, the attackers crossed the river and took the other half of the city. The Iraqi army and police, who vastly outnumbered their assailants, broke and fled, officers first, many of the soldiers stripping off their uniforms as they joined a flood of panicked civilians.

It was 10 June 2014, and Iraq's second biggest city, with a population of around two million, had just fallen to the militants of the group then calling itself Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham/the Levant (Isis or Isil).

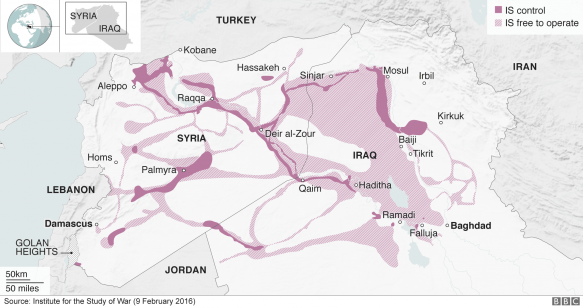

Four days earlier, black banners streaming, a few hundred of the Sunni militants had crossed the desert border in a cavalcade from their bases in eastern Syria and met little resistance as they moved towards their biggest prize.

Rich dividends were immediate. The Iraqi army, rebuilt, trained and equipped by the Americans since the US-led invasion of 2003, abandoned large quantities of armoured vehicles and advanced weaponry, eagerly seized by the militants. They also reportedly grabbed something like $500m from the Central Bank's Mosul branch.

How rich is IS?

Despite territorial losses, IS survives, thanks in no small part to its status as "the best-funded terrorist organisation" in history. While most people decry the validity inferred from the name of IS as a "state", the group's financing is certainly more reminiscent of a state than that of organisations such as al-Qaeda that relied heavily on donations to fund their operations.

Islamic State: The struggle to stay rich

"At the beginning, they behaved well," said Abu Anis. "They took down all the barricades the army had put up between quarters. People liked that. On their checkpoints they were friendly and helpful - 'Anything you need, we're here for you.'"

The Mosul honeymoon was to last a few weeks. But just down the road, terrible things were already happening.

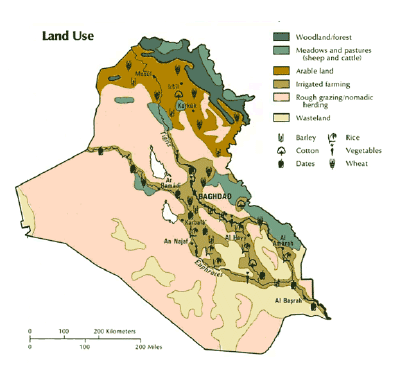

As the Iraqi army collapsed throughout the north, the militants moved swiftly down the Tigris river valley. Towns and villages fell like skittles. Within a day they had captured the town of Baiji and its huge oil refinery, and moved on swiftly to seize Saddam Hussein's old hometown, Tikrit, a Sunni hotbed.

Just outside Tikrit is a big military base, taken over by the Americans in 2003 and renamed Camp Speicher after the first US casualty in the 1991 "Desert Storm" Gulf war against Iraq, a pilot called Scott Speicher, shot down over al-Anbar province in the west.

Camp Speicher, by now full of Iraqi military recruits, was surrounded by the Isis militants and surrendered. The thousands of captives were sorted, the Shia were weeded out, bound, and trucked away to be systematically shot dead in prepared trenches. Around 1,700 are believed to have been massacred in cold blood. The mass graves are still being exhumed.

Far from trying to cover up the atrocity, Isis revelled in it, posting on the internet videos and pictures showing the Shia prisoners being taken away and shot by the black-clad militants.

In terms of exultant cruelty and brutality, worse was not long in coming.

After a pause of just two months, Isis - now rebranded as "Islamic State" (IS) - erupted again, taking over large areas of northern Iraq controlled by the Kurds.

That included the town of Sinjar, mainly populated by the Yazidis, an ancient religious minority regarded by IS as heretics.

Hundreds of Yazidi men who failed to escape were simply killed. Women and children were separated and taken away as war booty, to be sold and bartered as chattels, and used as sex slaves. Thousands are still missing, enduring that fate.

Deliberately shocking, bloodthirsty exhibitionism reached a climax towards the end of the same month, August 2014.

IS issued a video showing its notorious, London-accented and now late executioner Mohammed Emwazi (sardonically nicknamed "Jihadi John" by former captives) gruesomely beheading American journalist James Foley.

In the following weeks, more American and British journalists and aid workers - Steven Sotloff, David Haines, Alan Henning, and Peter Kassig (who had converted to Islam and changed his name to Abdul Rahman) - appeared being slaughtered in similar, slickly produced videos, replete with propaganda statements and dire warnings.

- Prev

- Next >>