Review of Amer Hanna-Fatuhi:

Review of Amer Hanna-Fatuhi:

THE UNTOLD STORY OF NATIVE IRAQIS: Chaldean Mesopotamians 5300BC-Present.

Xlibris Corp., 2012.

As his subtitle indicates, Amer Hanna-Fatuhi has undertaken an enormous challenge: to chronicle the history of the original inhabitants of Iraq over an extensive expanse of nearly 7000 years.

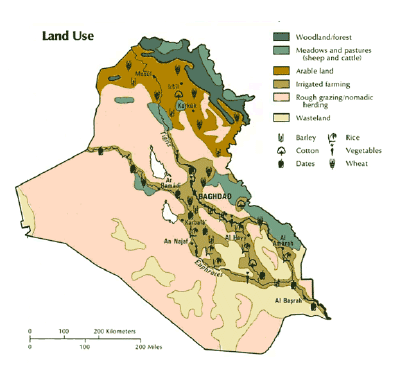

Most Americans first met the geographic area now known as Iraq in fourth or fifth grade, when they learned that the human race probably originated in the “Fertile Crescent,” formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. But for all practical purposes, that was where our knowledge ended. Any other information about Middle Eastern geography and the people who lived there largely disappeared – save for those who might have attended religious training classes, where they learned about the history and religious traditions of the ancient Hebrews. In this training, other references were occasionally made to Middle Eastern peoples who may have crossed paths with the Hebrews at one point or another.

However, an issue which has remained a mystery for the better part of nearly 7000 years is the general background and culture of these “other” residents of the area. Who were they? What were they like? What did they believe? What languages did they speak? Were they similar enough to communicate with each other? We learned from the Bible that they believed in numerous gods. But what else is there to know about them? Were their religious beliefs similar in any way to those of the Hebrews? Most of us never gave these issues a second thought.

At the end of the 20th century, we learned more about Iraq and the Middle East, but largely in the context of the modern world, and of issues related to Western society. We know that Iraq has been the target of two wars involving the U.S. But the people who live there, and their connections to those who lived there in the intervening 7000 years, remains a mystery to most Americans.

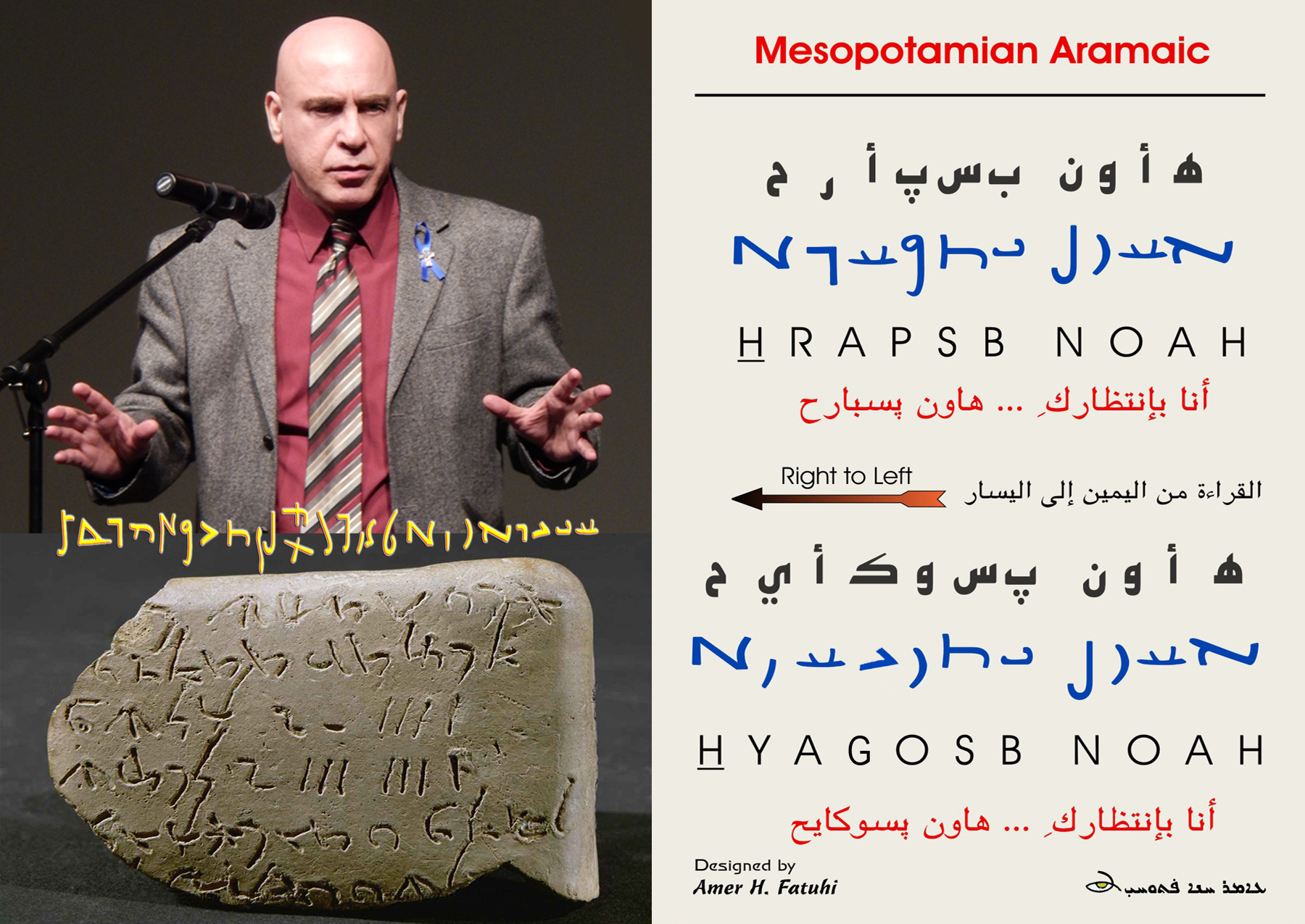

In this book, Hanna-Fatuhi attempts to provide a remedy to this information gap by discussing some aspects of the culture of the people who exercise a claim to being the modern day descendants of the people who inhabited Iraq over the many centuries when it was generally known as “Mesopotamia.” In the introductory chapters of the book, Hanna-Fatuhi sets the stage for the presentation of the Chaldean, Aramaic-speaking peoples of Northern Iraq (the area often known as Kurdistan) as the true indigenous people of Iraq (p. 47).

The author traces their history, beginning with the very earliest times, where he attempts to unravel the identities of the several people who are alleged to have been residents of Mesopotamia, and to understand what their relations to each other might have been. Many of these names (Sumer, Akkad, Babylon, Assur), he claims, referred to specific regions or locations. However, according to Hanna-Fatuhi, the entire, broader group of people was known as Chaldeans or Chaldees (also known as Kaldi or Kaldu, or in Hebrew as Kushdim or Kashdim, a name derived from their leader, Kush, father of the Biblical Nimrod. The author proceeds throughout the remainder of the book to provide a summary of the historical and cultural highlights of the Chaldean people.

He begins with the conquests of Sargon the Great, who inspired the Chaldeans of Akkad and Sumer to express their patriotism through military exploits in 2234- 2279 BC. His exploits were amazing, given the “humble means accessible at the time” (p. 49). Moving to even greater Mesopotamian leaders, he cites the great rule giver, Hammurabi, ruling from 1792-1750 BC. Needless to say, all subsequent cultures have gained much from his insightful Code. Jumping another 1000 years, he traces the recognized leaders of Babylon, with its famous Tower, its Hanging Gardens, and its connections to the Jewish people, some of whom remained in Mesopotamia/Iraq until the mid-20th century, when most left after the establishment of the Nation of Israel.

Much of this, of course, is already known. However, the modern reader is likely to be more interested in later sections of the book, which are devoted to the more recent history of the people of Iraq. The author devotes a considerable amount of attention to analyzing the various religious and linguistic divisions among the peoples of Iraq, He does indicate that the people of Mesopotamia shared several languages over time, but the fact that this was the case did not automatically mean they were part of the same genealogical or cultural group. Hence a key issue becomes the question of what constitutes a specific, identifiable ethnic people. A great deal of the book is devoted to this issue.

A key issue of the more recent time period focuses on the religious issues of Iraq and the surrounding area. Since Iraq was at the crossroads of the great religious changes which occurred as the Christian Era developed, the author devotes considerable attention to this issue. The author documents the version of some of the earliest Christian missionaries, and the ways in which the peoples of what was then Mesopotamia reacted to the new Christian religion. Most were introduced to the gospel of Jesus Christ by his Apostle Thomas, aided by his own disciple, St. Addai. In the earliest days, Christianity was largely a loosely united group of Jesus’ followers, all of whom claimed to teach the message of Jesus. As time progressed, however, leaders arose among the various groups, each of which held different views, largely based on their unique philosophical perspectives.

These, in turn, lead to doctrinal disagreements between the groups. Then follows a description of the various disputes within early Christianity, leading to numerous claims of heretical teachings among the numerous Christians sects. At that time, these divisions seemed more likely to occur between the churches of the East and the West. That these represented the major divisions is not surprising, in view of the fact that the basic philosophical perspectives of East and West were so different. The Christians of Mesopotamia were followers of Nestorius, whose teachings were declared heretical by the Western Church at the Council of Ephesus in 431 AD. Some communities of Christians in Mesopotamia later reunited with the Roman Catholic Church in 1553, forming what is now known as the Chaldean Rite of the Catholic Church. Different communities of Iraqi Christians seemed to associate with either the Western or the Eastern group over the centuries which followed, even into eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The growth of the Western-oriented Christians was encouraged by visits from Capuchin and Dominican missionaries in the 18th century (pp. 124-125). In the nineteenth century, an entirely new religious perspective came about, as representatives of various Protestant denominations, particularly the English, began to proselytize in Iraq, which by then was a British Protectorate. Other sections of the book are devoted to an analysis of various historical, archeological, and linguistic evidence for the background of the Chaldean people, as well as documentation of their accomplishments over the centuries.

Historians from a variety of perspectives undoubtedly will differ over many of the author’s claims, due to the difficulty of documenting, with certainty, historical evidence over so many thousands of years. However, all cultural groups, including the Chaldeans, have been subjected to such critiques of their claims to their historical connections. All groups are entitled to make the case for their own history. Amer Hanna-Fatuhi has provided a creditable statement of the claims of the Chaldean Mesopotamians to their place in history. His work provides a valuable resource to all people of today, whatever their ethnic background, who are curious to understand the historical connections of the modern nation of Iraq and its people, to its ancient historical connections to the Mesopotamia we were introduced to so many years ago in grade school.

Reviewed by Dr. Mary C. Sengstock, Ph.D.

Professor of Sociology

Wayne State University

Detroit, Mi 48202

Comments

RSS feed for comments to this post